Australian identity from the vantage of eternity // The Jindyworobaks, Part One

The Jindyworobak movement was an attempt to view Australian identity from the vantage of eternity. Lost to memory, Lucas Smith recovers the Jindies for the 21st century

The soul of a people is revealed in its poetry. This is perhaps especially true when they have little poetry to be proud of, or when its poets have forgotten that they belong to a people. This, however, they can never entirely do, because language is a shared heritage and inherently limited to those who can speak, read and understand it. What’s more, even the most ethereal, obscurantist post-modernist needs a community in order to be read. The act of poetry can never be solitary. Even if the poet writes only in a private diary set for destruction upon his death, the language still binds him to others.

Poets traditionally served a religious function, memorising the sacred myths of the tribe, and their reduction in the contemporary world to entertainers, however highbrow, mirrors religion’s slide into emotive, pseudo-cathartic entertainment. And what of the poet when he does not know who his people are? And what of the poet when his people stop listening?

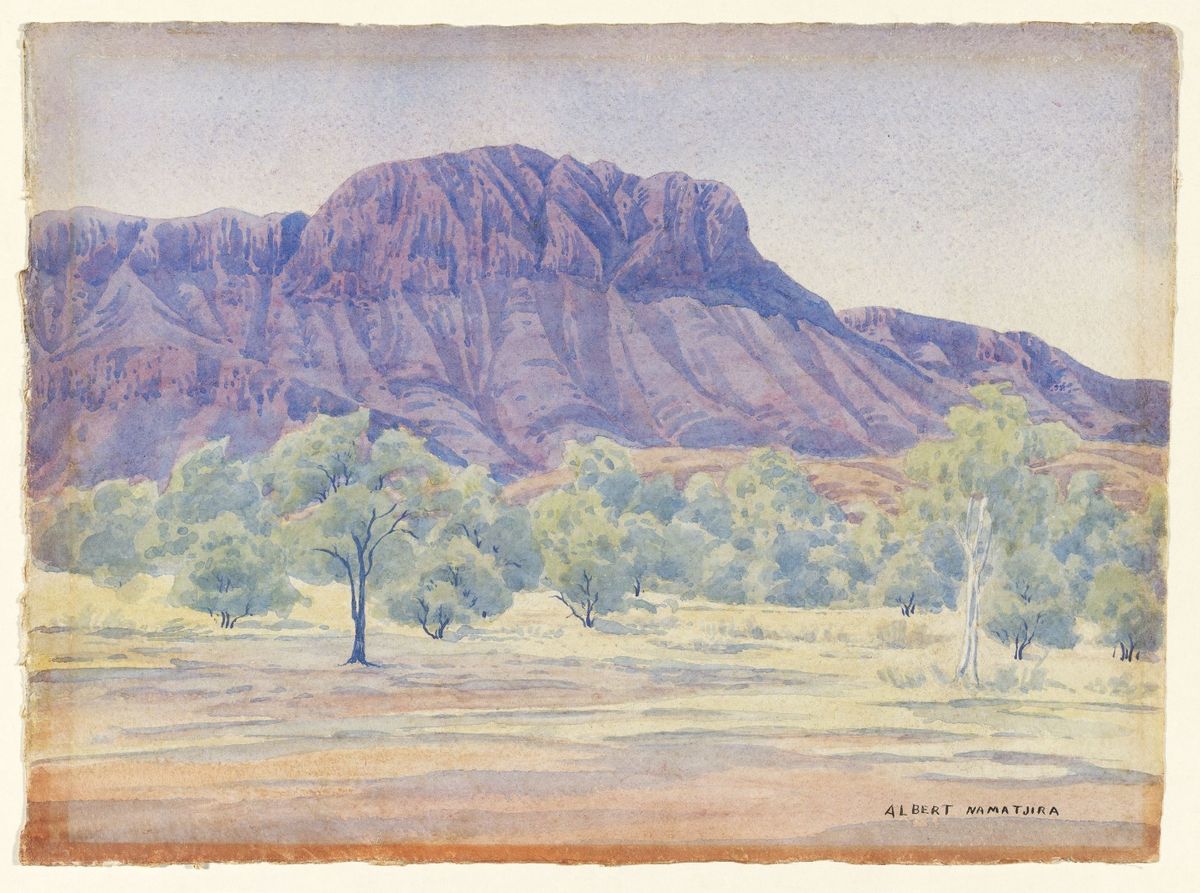

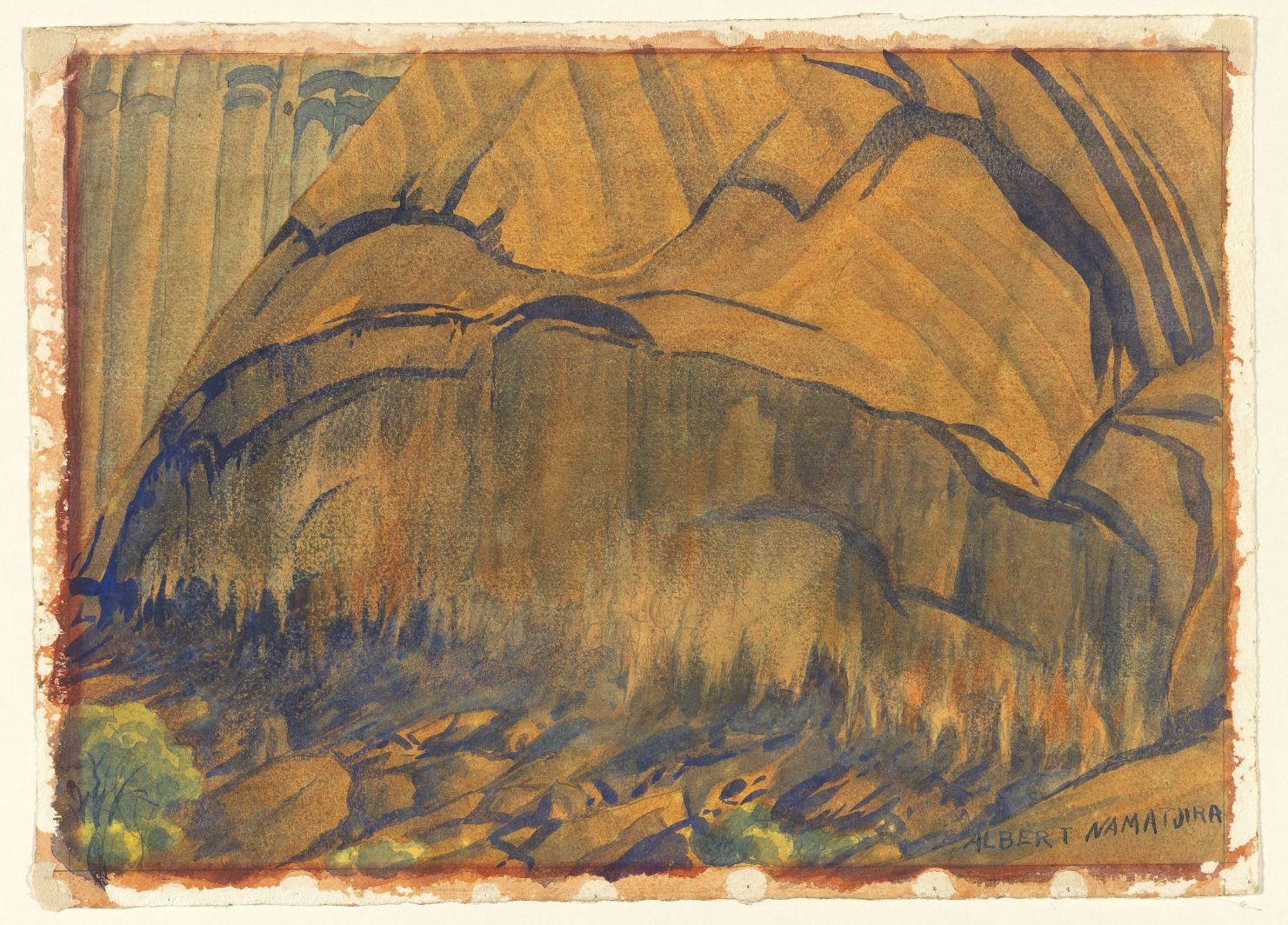

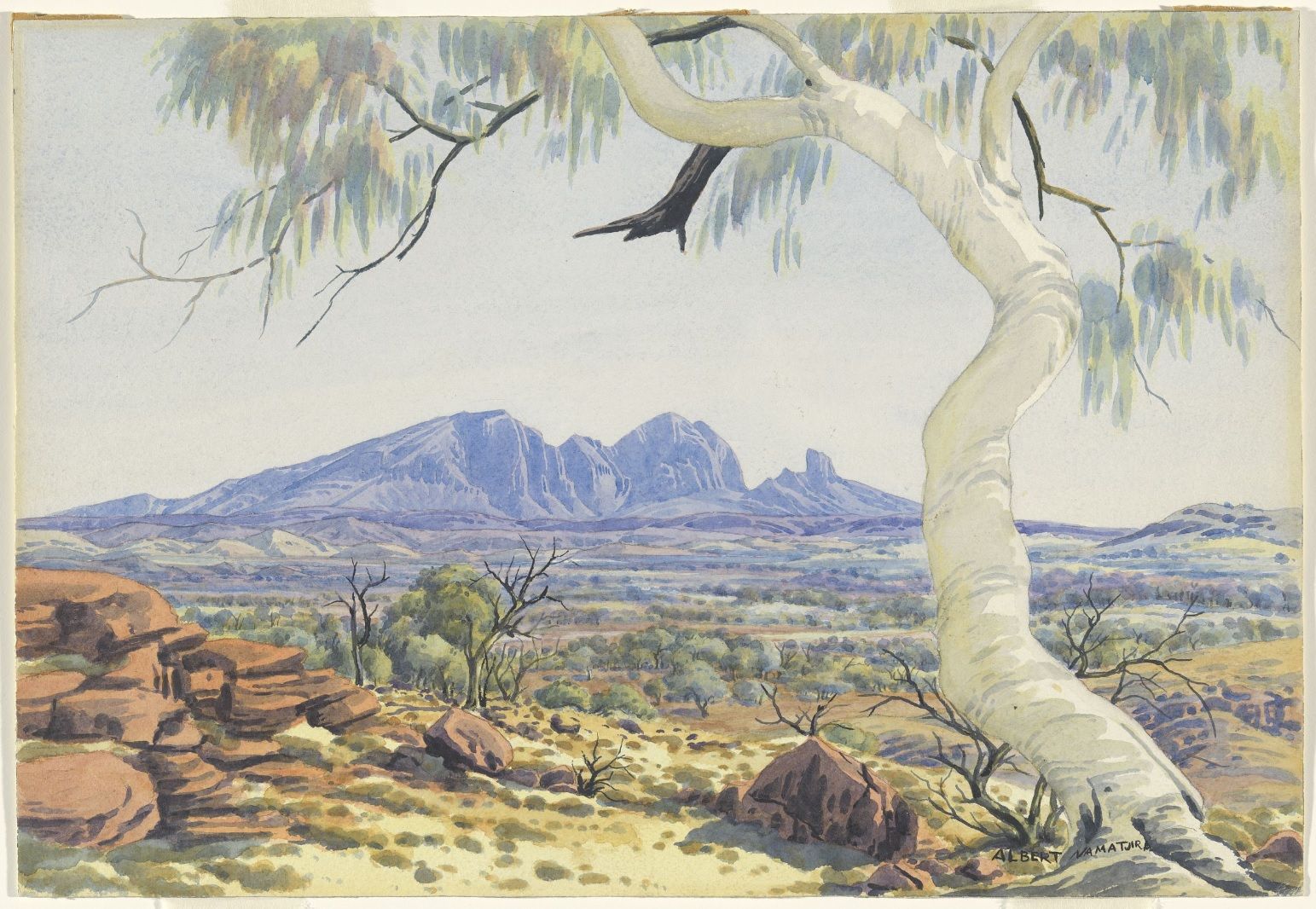

The Jindyworobak movement was a loosely connected group of poets active mostly in the 1930s and 40s who sought to renew the Australian imaginary, drawing on Aboriginal mythology and the particularities of Australian landscape, flora and fauna. The word Jindyworobak means “annex” or “join” in Aranda. Their goal was not to co-opt Aboriginal culture or pass it off as their own but to enter imaginatively into the reality that the Australian landscape has its own metaphysics. They are credited with introducing the concept of “the Dreamtime” to popular awareness, among other concepts, from mostly Central Australian Indigenous sources. The Jindyworobak movement later extended into painting and music but its foundational impetus was poetic.

The five principals of the movement, Rex Ingamells, Ian Mudie, Flexmore Hudson, William Hart-Smith and Roland Robinson, with a score of dilettantes in train, produced a yearly anthology from 1938-53, that also featured a number of other poets who were not fully aligned in philosophy or enthusiasm but nevertheless found some sympathy with the movement, including Mary Gilmore, Judith Wright and James McAuley. There was a Jindyworobak Club with a half-crown a year membership fee, whose members enjoyed twenty-five per cent off Jindyworobak book purchases.

Ingamells, Mudie and Hart-Smith were from Adelaide, then much more Capital of the Outback than it is today, removed not only from London and New York, but also Sydney and Melbourne, a reminder that innovation often comes from the margins even if it finds its fullest expression in the centre.

With the exception of Robinson, who interviewed and befriended numerous Aborigines along the Eastern seaboard, and used their stories in his work, nearly all of what they knew of Aboriginal life came from books: The Vanished Tribes by James Devaney, anthropological work by Ted Strehlow, R.M. Berndt, Spencer & Gillen and A.P. Elkin, among others. For this reason, their language and anthropology has often been superseded by more recent scholarship and none of them ever approached fluency in any Aboriginal language. According to Elkin, Strehlow was the only outsider to every be truly fluent in an Aboriginal language, being essentially a native speaker of Aranda, learning it along with German and English from the cradle in Hermannsburg, where his father Karl was the pastor.

The young Jindyworobak, as Brian Elliott writes in the introduction to his definitive The Jindyworobaks (University of Queensland Press, 1979), which is my main resource for this article, was in rebellion against previous generations of Australian poets: “He found it all weary, stale, flat and unprofitable; and worse, boringly unrelated to the experiences of wonder that were daily before his eyes…Above all there was no spirituality, nothing of a true bond between the man and his natural world in what the poets attempted to feel.”

Elliot is adamant that the Jindyworobaks were not merely transmitting or attempting to transmit Aboriginal culture or even documenting its history and law, but were, “missionaries—as I have unhesitatingly called them—their mission was directed not to the blacks, but to the whites, to the civilisation which exists now, and is in control.”

The Jindies (in typical Aussie diminutive), and Ingamells most strongly, sought to break with Europe. They were searching for something that was simply sensed, an inchoate feeling of something that hadn’t yet been put into words in Australia.

Hart-Smith tells how he was inspired to write: “In the stacks at Mitchell Library I came across some typescript MSS by David Unaipon, an Aboriginal—pastor, I think. His retelling of his people’s legends fired something in me. This sort of fused with my delight in, how shall I put it?—the Australianness of Australia. I began to write.”

There was in addition a strong undercurrent of despair over the darkness of the 1930s in Europe that led them to the beliefs that Ingamells states in the foundational manifesto of Jindyworobakism, Conditional Culture (1938):

Any genuine culture that might develop in Australia, however it might be refreshed and inspired by English influences, would have to represent the birth of a new soul. A fundamental break, that is, with the spirit of English culture, is the prerequisite for the development of an Australian culture…Its quintessence must lie in the realization of whatever things are distinctive in our environment and their sublimation in art and idea, in culture…Pseudo-Europeanism clogs the minds of most Australians, preventing a free appreciation of nature…Although emotionally and spiritually they should be, and I believe are more attuned to the distinctive bush, hill and coastal places they visit than to the European parks and gardens around the cities, their thought-idiom belongs to the latter not the former. Give them a suitable thought-idiom for the former and they will be grateful. Their more important emotional and spiritual potentialities will be given the conditions for growth. The inhibited individuality of the race will be released. Australian culture will exist. [Emphasis mine.]

From the beginning the Jindies had their critics, most trenchant among them, A.D. Hope, who insisted on the essentially European character of Australians and Australian culture and derided them as “The Boy Scout School of Poetry”. Less polemical and more insightful is cultural historian Geoffrey Serle, who writes that the Jindies, “Being so preoccupied with the surface features of the countryside, they unwittingly reflected the English Georgian poetry they so vehemently condemned; and they were retreating into isolation from a mad world.”

Even among the five principals there was important disagreement. A tone of loyal opposition is struck by Hart-Smith:

Mr. Ingamells’s stressing of the cultural importance of the Aborigines is sheer primitivism, a sentimental glorification of a far distant stage of human development … There are in it, too, hints of a windy Platonic doctrine of recollection and of a Spenglerian conviction that modern society has degenerated … It is for the Jindyworobaks now to show how the Aborigines’ way of life offers a solution to our problems or even a balm for our hurts. I cannot see that they have done so yet. This idealizing of our Aborigines is, to my mind, escapism.

There was indeed a strong current of Spenglerian pessimism in Ingamells, that showed in his less happy attempts at verse polemic, such as this example from “The Gangrened People”:

We, the Gangrened People,

swollen up with fabricated virtue,

virus of hypocrisy,

call ourselves the champion of Justice

and Liberty and O Democracy.

This is questionable as polemic but definitely bad poetry, as is much of Ingamells' work. However, he also wrote the most striking and melodious piece of Jindy verse, “Moorawathimeering” a piece that seems almost designed to drive Hope back to the tantalus (although Hope himself would use Aboriginal place-names to great effect in his poem “Country Places”). And yet, because of its music, it works. For best results, read aloud.

Into moorawathimeering

Where atninga dare not tread,

Leaving wurly for a wilban,

Tallabilla, you have fled.

Wombalunga curses, waitjurk—

Though we cannot break the ban,

And follow tchidna further

After one-time karaman.

Far in moorawathimeering

Safe from wallan darenderong,

Tallabilla waitjurk, wander

Silently the whole day long.

Go with only lilliri

To walk along beside you there,

While douran-douran voices wail

And Karaworo beats the air.

One can easily tell that this is a lament (for an exiled murderer, as it happens). The mystery of the words, the alienation from meaning, along with the flowing rhythm, is part of the point. Ingamells can hardly have expected the average reader to know the meanings of the words. In a way the Aboriginal words serve the same purpose as the nonsense in the choruses of Irish folk songs, an invitation to be lost in rhythm, and in the Anglo-Australian reader an invitation to further investigation.

At their best the Jindies were poets thinking through the implications of being European on this continent. Take “Intruder” by Ian Mudie, which is not the smoothest prosody but concisely expresses a thought that must have occurred to just about every Australian at some point. It is brief enough to quote in full and incidentally shows that the Jindies were among the first practitioners of literary modernism in Australia:

When I walk

I do not know

What ancient sacred place

My foot may desecrate

Or if my tread shall fall

Where some cult-hero bled,

Or shed blood,

Or gave fire to man

In the far dreamtime.

Vanished elders

Of the long-dead tribe,

Forgive

My taboo-breaking,

My uncicatrised intrusion;

And do not send

Kadaitcha men

To haunt my dreams

Surely you can guess

My conscience

Is uneasy enough

Already.

This is far removed from the Australian ballad tradition, Wordsworth with gumtrees and Sunburnt Country kitsch. Significant in “Intruder” is the present-tense, “do not send”. A perpetual presence lingers. Contrast this with a nineteenth century example taken more or less at random, Henry Kendall’s “September in Australia” from 1869.

Grey winter hat gone, like a wearisome guest,

And behold, for repayment,

September comes in with the wind of the West,

And the Spring in her raiment!

The ways of the frost have been filled of the flowers

While the forest discovers

Wild wings with the halo of hyaline hours,

And a music of lovers.

September, the maid with the swift, silver feet!

She glides, and she graces

The valleys of coolness, the slopes of the heat,

With her blossomy traces.

Sweet month with a mouth that is made of a rose,

She lightens and lingers

Perfectly serviceable Victorian verse but aside from spring in September there is nothing identifiably Antipodean, either in fact or mood. Much early Australian verse, although not all, is like this, with hardly a mention of gum trees or kangaroos. How much this matters has long dominated debates about art in Australia.

Beyond the superficialities (which of course are never merely superficialities) of distinctive plants, birds and the like, Mudie hearkens to a primal source, most explicitly in his short poem “Underground”.

Deep flows the flood,

deep under the land.

Dark is it, and blood

And eucalypt colour and scent it.

Deep flows the stream,

Feeding the totem roots,

deep through the time of dream

In Alcheringa.

Deep flows the river,

deep as out roots reach for it;

feeding us, angry and striving

against the blindness

ship-fed seas bring us

from colder waters.

Deep flows the flood. The Biblical overtones here are obvious. In addition to the sense of discovery of the Australianess of Australia, is the need to keep away outside influences, “the blindness” of “colder waters”.

“Avenger” by Hart-Smith builds on Mudie’s feeling of foreboding, imagining an aggressive presence bent on revenge.

It is he who had a name but yesterday,

This presence in the night that fills me so with dread.

Those are his eyes which peep

Down through the swaying branches;

Those are his feet

Which softly tread the leaves among the stones,

Breaking a stick, a brittle stick

Brittle as bones.

He it is who is not yet buried,

Whose body is not yet put away,

Whose breath is in the leaves of all the trees.

Yet this powerful presence is vanquished by the speaker of the poem.

His spears were true,

Yet my shield was swift as a darting bird,

Swift as the spear which struck when his shield faltered,

Faltered as the wings of a bird which is struck in the air.

In another poem “April 28th, 1770”, the date Captain Cook first sighted Australia, Hart-Smith shows an acute awareness of the metaphysical cataclysm unleashed by British settlement.

Before That came bearing them,

before this new thing happened,

day followed night without question,

tide followed tide and wave followed wave,

breaking at my feet,

and I made the wave’s voices say what they would.

Now they are asking the question,

and turning over the question,

breaking up the question.

Hart-Smith was also the most intentionally comic of the Jindies. One of the few notes of comedy in their whole oeuvre incidentally coincides with one of the few mentions of Christianity. In “Mary” a bishop is visiting an outstation by camel, seven hundred miles from his Cathedral.

“Mary,” he said, “do you pray to God?”

“Yes,” smirked she, “Me talk-talk

Longa that cranky beggar!”

The best and most enduring Jindy was Roland Robinson, according to Les Murray. He did his own research, living for long periods of time in the bush with only what he could carry on his back. Robinson’s attentiveness to nature is keener than the rest and his intimacy with rocks, water, flora and fauna unfeigned, not brought in for other purposes, as it were. Robinson also, as Elliott points out, can lay claim to the astonishing distinction of being, “the only Australian poet ever, perhaps, to carry the whole of his repertoire in his head; he has always scorned poets who could not remember their verses and speak them, as well as print them.” In this ability he had ample company from countless generations of Aborigines. “And the Blacks Are Gone” is representative of most of Robinson’s work, which really deserves his own essay.

But this sea will not die, this sea that brims

Beyond the grass tree spears and the low close scrub,

or lies at evening limitless after rain,

or breaks in curving lines to the long golden beach

that the blacks called Gera before the white man came.

And the blacks are gone, and I frighten the crimson wing

and the wallaby in gullies where the rock-pools lie

fringed by acacias and stunted gums. And I come

out on to open ridges flowering before this sea.

And the blacks are gone, and we are not more than they,

To-night as I make my camp by the rain-stilled sea.

Born in Ireland, Robinson was most able to connect Aboriginal mythology to old World analogues, especially Celtic mythology. His use of the Dreamtime is held lightly, more as a guiding principle for seeing the land and its creatures, whereas for the others it is an over-defined “Alcheringa”, which ironically highlights its alien-ness.

The collective body of Jindy work was an attempt to integrate Australia’s Aboriginal, colonial and modern histories into one. To quote Elliot again: “Jindyworobak Dreamtime is ‘Australia’s history’ as a whole … That is, it is the national identity viewed sub specie aeternitatis.” Their aim was nothing less than to forge a new nation with their verse. Who can imagine such ambition today?

If the culture of the 1890s produced Henry Lawson, Banjo Paterson, Barbara Baynton, Joseph Furphy, Miles Franklin—who showed Australian society to itself on its own terms for the first time—the Jindyworobaks were more internal, brooding on the deep and perhaps repressed experience of displacement (from Britain) and settlement.

If the cultural ferment of the 1890s paved the way for Federation, as Henry Parkes believed, then the Jindies perhaps foreshadow our own moment of cultural uncertainty, when Australia seems less and less like a nation-state and more like an economic zone. They were plumbing the depths, both of psychology and of the continent’s pre-European history.

It’s hard to think of parallel movements with other nations, although there must be some. The American confrontation with their own Native peoples was more forthright, aggressive and somehow more honest than the Australian, such that American military hardware is still named after Native American tribes and persons. Although American poets used Native influences, stories and themes, it was not as intensely tied up in a socio-political project like the Jindyworobaks. Lament for a fallen adversary is sometimes present, but very rarely is the type of anxiety expressed by Australian writers. The Great Australian Silence, which was never universal, cast a long shadow over cultural development and ensured a certain diffidence in its twentieth-century descendants.

As might be imagined, the lasting results of the Jindies were mixed. Their limitations were recognised even by their own. Robinson articulates the speculative character of the movement after listening to the screeches of Black Cockatoos: “So shall I find me harsh and blendless words / of barbarous beauty enough to sing this land.”

Those who embody a culture most fully are usually the naïfs, the natural, the William Blakes and Cathedral architects of this world. And yet it is an irreducible part of the Jindyworobak effort that its limitations were built into its own idea of itself. They could not, not ever, enter into the mindset of the Aborigines, as they freely acknowledged. That much is self-evident. The movement was theoretical before it was actual, and this was its downfall. Indeed this is the Gordian knot confronting Australian, and perhaps all post-colonial, artists.

How to overcome self-awareness? It is said that in Scotland it takes seven generations to produce a master bag-piper. We are now in the eight or ninth generation of native-born Australians. To be successful, even as they embrace the world, they must be conscious of no other home than here.

As an explicit movement Jindyworobakism petered out in the 1950s, after the death at forty-two of Ingamells, who was always the organisational and spiritual driver of the movement. But its seeds are evergreen, like eucalypts, and Jindy resonances will exist as long as there are people on this continent. The spiritual deficit they recognised was real but they were hasty in finding a solution. Any honest artist knows that he is not fully in control of what he does. None of the Jindies were Christian and it is no coincidence that the broadest flowering of the seeds they planted is found in Les Murray, who was. Upon Murray’s death in 2019, in an extraordinarily happy statement that ought to be trumpeted nationally at every opportunity, Noel Pearson called him, “the poet of my country and my people. The Australia that began more than 60,000 years ago, not just the one invented in 1788.” Murray’s achievement and fulfilment of Jindyworobakism, as Christ fulfils the pagan religions, is the topic of the next article in this series.