1. What they mean when they talk about synodality

Three books on synodality, pitched at different levels, shed light on what synodal theology actually involves.

Orm Rush: The Vision of Vatican II: Its Fundamental Principles (2019) Rafael Luciani: Synodality: A New Way of Proceeding in the Church (2022) Anne Benjamin & Charles Burford: Leadership in a Synodal Church (2021)

Read the previous section: 0. Introducing Synodal Investigations.

WHAT IS SYNODALITY? As the continental stage takes shape there are two broad positions. Either synodality is the fulfilment of the vision of the Second Vatican Council’s “People of God” ecclesiology, and therefore an end to what Massimo Faggioli calls “Vatican II nominalism”. Or in the words of the departed Cardinal George Pell, it is a “toxic nightmare”, the revenge of liberation theology, neo-Marxism, extreme secularism and so on, heresies suppressed during the last two Pontificates and now returning from the margins to the centre.

It is the last laugh of “rupture” over “continuity and reform”, to use Benedict XVI’s language; or it’s the grace-filled and long-awaited victory of co-responsibility, radical inclusivity, tolerance and love over hierarchy, patriarchy and secrecy. It will be the liberation of the true theology and doctrine of the whole church from centralised discipline; or perhaps the lifting of the lid of Pandora’s Box.

Polarisation of this sort ignores the plain words of Cardinal Kasper back in 1989. Writing after the Extraordinary Synod of 1985, at which then-Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger began a crystallisation of the interpretation of the Council, Cardinal Kasper made the task for Catholic theology clear: the council itself is no longer in question. The only dispute is about interpretation—a subdiscipline of theology and philosophy with the unfortunate name of hermeneutics. While its growth is sometimes attributable to biblical interpretation, hermeneutics ultimately began with Nietzsche: “There are no facts, only interpretations, and this too is an interpretation.”

If you want to know more about hermeneutics, there’s a good encyclopedia article on Hans-Georg Gadamer, the leading (but not only) philosopher of hermeneutics, whose Truth and Method (1960) has become something of a standard text. Two of his ideas are important to grasp at the outset for a short review like this. One is “pre-judgment” or prejudice: that people’s “situatedness”, their subjective starting-points in any enterprise, are not negative even when they are not what an ordinary person would call reasonable. You have to start somewhere, and no starting point is ultimately an impediment to understanding, because as you proceed in dialogue even your own starting point can be understood differently. In Gadamer’s thought, prejudices therefore have a positive meaning—tradition, authority and the like can be just as good a starting point as scientific modes of reasoning, provided the person is open to dialogue with others. That’s the second major point:

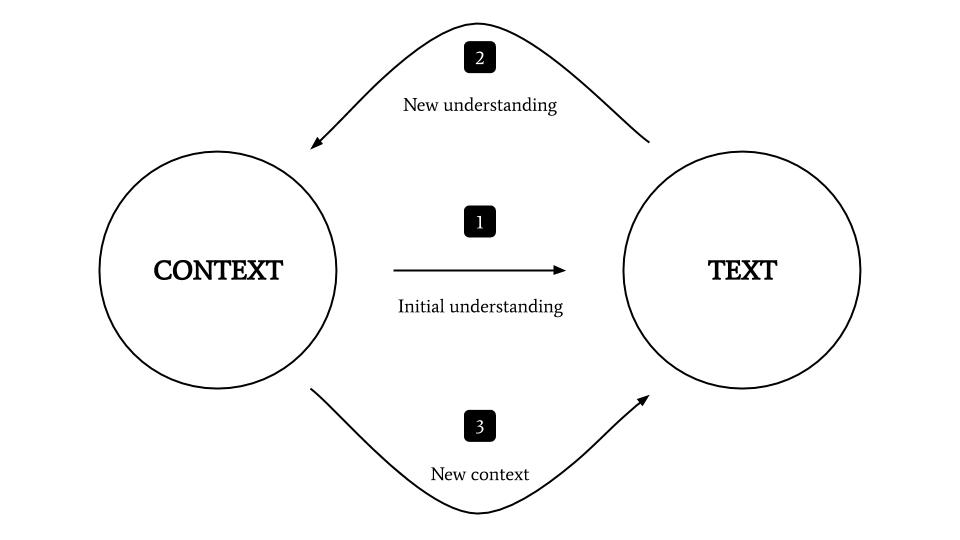

For Gadamer and other philosophers of hermeneutics, there is no possibility of a “plain” reading of any text, like Scripture or the documents of a council. When I read something, I bring my own understanding to it. The text then changes my understanding dialogically, helping me see my context in a new light. I then see something new in the text as a result, and the circle continues. This dialogue takes place in communities too, so understanding is fundamentally a community effort. Circularity is the governing theme of hermeneutics, and is central to synodal theology too.

In this review, the first part of an ongoing project to understand and critique the aims and methods of synodality, I will break down three recent representative books on the topic pitched at different readers: Fr Ormond Rush’s book on the theology of reception, The Vision of Vatican II (2019), Rafael Luciani’s Synodality (2022) and a guidebook to contemporary Catholic leadership, Leadership in a Synodal Church (2021), co-authored by Anne Benjamin and Chares Burford.

My basic thesis is this: synodality is the triumph of hermeneutics as an ecclesiological style. Traditionally the church has been thought of as the “pillar and ground of the truth” (1 Tim 3:15), with doctrines and a deposit of faith that are to be guarded (1 Tim 6:20, Dei Verbum 10). But hermeneutics is not precoccupied with the truth. Its domain is rather meaning, or questions like, “What do I understand to be true?” After decades of struggle over the interpretation of Vatican II, between what Pope Benedict XVI in 2005 called the “hermeneutic of discontinuity and rupture” and the “hermeneutic of reform and continuity”, the new synodal theology avoids altogether the attempt to close the question explicitly. Instead it elevates the process of interpretation to the first position, transforming the church from an ecclesial community into a community of interpretation, in which the act of interpreting the faith becomes the constitution of the church.

Fr Ormond Rush’s The Vision of Vatican II: Its Fundamental Principles

Prior to the synodal process really kicking off, if you asked who Australia’s pre-eminent theologians were, you’d have to say Professor Tracey Rowland, 2020 winner of the Ratzinger prize alongside Jean-Luc Marion, and Sr Isabell Naumann ISSM, who sits on the Vatican’s International Theological Commission. But in terms of raw impact, Fr Ormond Rush, a priest of the Diocese of Townsville who lectures at the Australian Catholic University and holds a doctorate from the Gregorian University, is now definitely among those of first rank.

He has been a key figure in setting the groundwork for the theology of synodality, and was an expert on the Frascati group that drafted the Document for the Continental Stage. His three major works since 2004 have concerned the theology of Vatican II’s reception, the centrepiece of the synodal programme: Still Interpreting Vatican II: Some Hermeneutical Principles (2004), The Eyes of Faith: The Sense of the Faithful and the Church’s Reception of Revelation (2009) and his magnum opus, The Vision of Vatican II: Its Fundamental Principles (2019).

The Vision of Vatican II attempts to fulfil Cardinal Kasper’s dictum that only the interpretation and reception of the council matter, by presenting a comprehensive list of principles by which Vatican II must be interpreted, and without which its “vision may be misreceived” by the church. Fr Rush gives 24 of these principles—48 really, because each principle is a binary pair. These principles,

“in effect, are reconfigurations of the way the Catholic Church has previously articulated various dimensions of doctrine and church life, which Vatican II judged to have become imbalanced. Accordingly, each principle proposes a proper balance between two aspects of doctrine or church life that the council wanted to realign. That the ecumenical council authoritatively promulgated these realignments to be normatively ‘constitutional,’ in the sense of ‘fundamental,’ for the Catholic Church is captured by the weight of the term ‘principle’.” [Emphasis mine. I’ll bold parts of quotations throughout this review.]

Fr Rush groups the principles into three categories: hermeneutical, theo-logical (I’m ignorant as to why he hyphenates it), and ecclesiological. Hermeneutics comes first—principles of interpretation—then theological and ecclesiological principles. The theological principles “hover” over the ecclesiological as meta-principles—so essentially as yet another set of hermeneutic criteria.

Each of the 24 binary pairs of these principles is to be understood in the sense of a hermeneutical circle, rather a dialectic or antinomy. One constitutes and gives meaning to the other in its binary pair, and to all the other principles, forming the “polyhedric” relationship that has been a motif of Pope Francis’ papacy. Nevertheless in these pairs each term is not necessarily equal: “Vatican II made explicit decisions regarding the proper balancing of the relationship between the two terms, groups, or roles”.

To illustrate:

The documents of Vatican II must be interpreted in the light of the historical event (the council) that produced them, and the historical event must be interpreted in the light of the official documents that it promulgated.

In this first principle Fr Rush cuts off the entire approach to Vatican II promoted by the children of St John Paul II—for instance, Opus Dei and priests influenced by them. The idea that one can be faithful to Vatican II simply by reading or quoting the texts verbatim, and by treating them as a rule to moderate the excesses of the postconciliar church, is from the outset rendered totally naive.

Take the Constitution on the Liturgy, Sacrosanctum Concilium, which is most often used by conservatives to show the legitimacy gap in the liberal interpretation of the council. Conservatives will point to this document’s “traditional” passages as evidence that the liturgical reforms of Annibale Bugnini were contrary to the desire of the council fathers (and maybe even Paul VI), and that the “reform of the reform” position was closer to what the council intended. How many times have young conservative Catholics heard (or told one another) that Sacrosanctum actually asked for the retention of Latin, Gregorian Chant, the removal of artworks “repugnant to faith, morals, and Christian piety” and so on.

Yet as Massimo Faggioli has argued in True Reform: Liturgy and Ecclesiology in Sacrosanctum Concilium, that same constitution can also be read as the “hermeneutical key” to the entire council, and in particular its ecclesiology. For Faggioli, liturgy after Vatican II returns the church to the patristic notion of the liturgy as sacrament of unity, leading to rapprochment with the world, within the church between laity and clergy, between Christians and other religions—and thus to a vision incompatible with the preconciliar liturgical imagination. Retaining the Tridentine rite alongside the new order of Mass is, on this reading, simply impossible without misreading what Vatican II was trying to do. This position is hardly marginal; it can be seen in the Holy Father’s liturgical documents Traditiones Custodes and Desiderio Desideravi.

So to return to Fr Rush, the documents do not stand alone, but are “finished in their unfinishedness” because there is both a contextual background in their authorship, and also a foreground in a hermeneutics of the reader who “receives” the documents. That means there is a “surplus of meaning” in the texts that may go beyond authorial intention or what is actually in the documents themselves.

These interpretations may be legitimate if they adhere to the vision of the council, or may be illegitimate if they don’t. The liturgical reform is one such legitimate fruit, even where it goes beyond the documents. Synodality, as the reader discovers in the epilogue to the book, is another. It is, in fact, the holistic fulfilment of the council’s vision despite never being mentioned in the texts itself; it is the “surplus meaning” of the council.

The remaining five of Fr Rush’s pairs of hermeneutical principles unfold in a similar way. These summaries/explanations are mine:

Pastoral/Doctrinal: Vatican II reorders the magisterium according to a “principle of pastorality”. There is no “doctrine” apart from its reception by the People of God. This can perhaps be seen in Pope Francis’ best-known statement about homosexuality: “Who am I to judge?”, or in the controversy over Amoris Laetitia’s footnote on communion for divorced and remarried. Whatever the church’s doctrine, it is expressed in a pastoral way —bringing people in, comforting them, giving them new possibilities.

Proclamation/Dialogue: Proclaiming the Gospel involves “dialogic openness to the perspectives and contexts of the intended receivers of the proclamation, whether they be believers or nonbelievers”. As in all hermeneutical exercises, meaning is both given and received; the recipients of the Gospel are not passive, but active participants in their own evangelisation—another element in which Sacrosanctum Concilium models the rest of Vatican II. Here one can also see the renewed emphasis on inculturation, eg. the Synod on the Amazon.

Ressourcement [going back to the sources]/Aggiornamento [bringing up to date]: The church does not just “resurrect” tradition in an antiquarian or nostalgic way, but rather renews itself by “re-receiving many of the past forms and practices of the tradition” with a mind to “critical adaption” for current times. This critical adaptation takes place in concert with the other principles, eg. pastorality, dialogue, reception and so on.

Continuity/Reform: The church is in continuity with the past, but does indeed prioritise certain breaks with previous tradition (As John O’Malley wryly asked in one essay, an over-emphasis on continuity might lead us to query, Did Anything Happen at Vatican II?) For another theologian of synodality, Peter Hünermann, the council intended four serious ruptures with the past: with integralist notions of Christendom, with the division between Eastern and Western Christianity, with the division from Protestants, and with anti-modernism, or what he calls “lingering on the threshold of the modern”.

Vision/Reception: Vatican II proposed a vision, but this must continue to be received in light of the church’s entire tradition, the “signs of the times” of the “globalised world so different from the world of the 1960s”. As Fr Rush writes, “it is they who will live it (or resist it).” But reception must be guided and balanced against the other principles, especially pastorality.

Fr Rush’s remaining 18 principles sit underneath these six, and deal with theological pairs (eg. Revelation/Faith) and ecclesiological pairs (eg. Scripture/Tradition, People of God/Hierarchy). This isn’t an academic paper, nor is it a comprehensive summary of the book, so the interested reader can seek out Fr Rush’s very fine work for themselves. But two things bear mentioning. Although they are presented as a list, the synodal readjustment has shown that not all are of equal importance. The pair People of God/Hierarchy is the most crucial in terms of the application of synodality, because it is the place where the prior tradition’s ecclesiology can be carved at the joint, as I will show with Luciani.

Second, the hermeneutical principles are of far greater importance than the theological or ecclesiological ones—not just for interpreting Vatican II, but indeed for Christian life more broadly in the postconciliar age. This is because, according to Fr Rush’s epilogue, “Receiving the Vision”, Vatican II inaugurated a new way of understanding the development of doctrine:

“Vatican II was an event of accelerated and concentrated ‘historical development’ over four years, when the council appropriated much of the ressourcement scholarship and pastoral experience of the previous three decades. Using a more critical hermeneutical model than the organic one of ‘development’ [advanced by John Henry Newman], Vatican II was an event of ecclesial conversion to a new style of being church ad intra and ad extra and a conversion of the Catholic imagination regarding faith and history.”

He then goes on to say that synodality, despite never being mentioned in the Vatican II texts themselves, represents the culmination of the vision of the council and a new stage in its reception. The council has been received by the Papal authority and by theologians (although more work is obviously to be done) but must now be received spiritually by the whole people of God according to the idea of the sensus fidei fidelium, the notion that the church subsists by faith primarily in the whole People of God and not just the hierarchy.

The people are therefore not merely passive objects for evangelisation, but theological subjects who must themselves be listened to (hence the emphasis on a “listening church”) to discern whether the church is actually being faithful to its mission. Therefore there cannot be any faithful reception of Vatican II without at least some species of synodality.

Before moving on to Luciani’s Synodality: A New Way of Proceeding in the Church, I think the implications of Fr Rush’s book are very clear:

- Vatican II was an event that broke with the past tradition in ways so significant as to introduce a new style of Christian life, such that to be intelligible it requires a new hermeneutical framework.

- This new hermeneutical framework is not to be found in the documents of the council alone, but in a set of meta-principles derived from the context of the council, the documents and their subsequent reception by the whole People of God.

- Synodality is the mode by which these meta-principles are actualised; an ecclesiological style not mentioned at all in the documents, but derived from their “surplus of meaning”.

- If synodality is the church’s new concrete ecclesiological style, yet cannot be found anywhere in the council documents, then the hermeneutic meta-principles derived from them and detailed in Fr Rush’s book are better guideposts to the church’s future than the documents themselves (or indeed the Scriptures, tradition and so on).

- These meta-principles then inform our ongoing understanding of their source, Vatican II, which is held to be a radical event requiring new principles etc…

So as I have already said, synodality is the triumph of hermeneutics as an ecclesiological style. Instead of a church as a community governed by ordained ministers, we instead have a “community of interpretation” arranged in a circular fashion. As far as the synodal process is concerned, this sense of circularity is part of the formal process, during what are called “restitution” stages. At this point documents from each stage are returned to earlier stages for comment and confirmation.

One only has to think of the corresponding liturgical incarnation of this idea, namely the postconciliar “church in the round”, in which the members of the community are equidistant from the altar. A good example is the (quite beautiful) circular church in Woy Woy affectionately known as the “Vati-can”. The aim is clear: despite the “protagonism” of the priest in the synaxis, he stands within the people of God, not before them. Every position around the altar is equal; there is no sense of hierarchy, linearity or the like.

The remodelled Parramatta Cathedral is another Australian example, with the altar centred and the other elements of the liturgical synaxis “deconstructed”. The central altar, decked out in the Benedict XVI-era style with ministers in gothic vestments, at times looks almost like a piece of performance art being staged in a gallery. Or perhaps an operating table in a teaching hospital, upon which the eucharistic body is dissected for observation.

Rafael Luciani’s Synodality: A New Way of Proceeding in the Church

Rafael Luciani, a Venezuelan theologian, published Synodality: A New Way of Proceeding in the Church in 2022. He is no less prominent than Fr Rush in the synodal process, as an expert on the theological commission of the synod secretariat. He is also a peritus for the Latin American Episcopal Council (CELAM) from which much of the synodal project is derived. His book was blurbed by Cardinal Kasper, and introduced by another leading theologian of the Tübingen school, Peter Hünermann, who was a leading signatory to a 2011 letter that prefigured the German synodal way, calling for an end to priestly celibacy, women’s ordination, and the democratisation of the church.

Luciani gives a frank comprehensive picture of what synodality means, the goals of synodal reform, why synodality is the only true reception of the Second Vatican Council, and what practical steps must be taken. Most importantly, though, is that Luciani does not shy away from admitting the consequences of synodal ecclesiology for Christians who were faithful to the teachings of the last two pontificates. During the Ratzinger years—first as head of the CDF, and then as Pope—Luciani says the correct reception of Vatican II regressed:

“…the papacy and the episcopacy began to be understood as distinct subjects in relation to the people of God. There was a regression to a pyramidal conception, one that understood the diverse modes of participation in the Church as deriving formally from the communio hierarchica, and consequently discarded the theology of the sensus omnium fidelium. This resulted in a notion of lay responsibility as an ancillary exercise and in the juxtaposition, still not fully resolved, between episcopal collegiality and the primacy.”

In Luciani’s view there were other regressions: the “progressive deflation of the value of local cultures as normative for reinterpreting tradition, doing theology, and transmitting faith”, centralism in governance and doctrinal development, and the belief that the universal church was prior to the local church in an essential sense. This led to an unacceptable homogenisation and hierarchicalisation of the Catholic Church that sat outside the authentic development of doctrine, such that the documents of that time are rendered suspect: Apostolos Suos, De Synodis Dioecesanis Agendis Instructio, even Pastores Dabo Vobis, the document that has done more to revitalise Australian seminaries than any other. And, of course, the Catechism of the Catholic Church and, one assumes, Ordinatio Sacerdotalis.

The pontificate of Pope Francis marks a reversal in this trend and a return to what might be called “Vatican II norms” in keeping with the hermeneutics of Fr Rush. According to Luciani, “the pontificate of Francis has inaugurated a new phase in the reception of Vatican II, one rooted in the ecclesiology of the people of God, understanding the normativity of chapter 2 of Lumen Gentium in the process of reconfiguring the whole Church.”

Again: the entire baptised people of God (the subject of Lumen Gentium’s second chapter) are the subject of the spiritual reception of Vatican II, as Fr Rush put it. So the JPII/Ratzinger years, by treating the reception of the council as a top-down affair, have simply misreceived the Council and thus set themselves outside the authentic postconciliar tradition. So the documents can be safely relativised. To take an example: from the synodal perspective, who cares if St John Paul the Great decided that women’s ordination was permanently off the cards? The pope, the bishops, the curia—they do not substitute for the whole people of God in receiving the faith. If there is a general sense in the church that women’s ordination is a call from God…

Again, the possibility of a plain reading of the documents is precluded by the synodal theology. Ironically, however, the synod secretariat’s own official documents tend to emphasise a “plain” and at times even conservative reading of Lumen Gentium that is not true to the more radical theology of the secretariat’s big thinkers. The official texts insist that synodality is a relative of episcopal collegiality and communion. This theme was seen most recently in the 26 January letter to Bishops from Cardinals Mario Grech and Jean Claude Hollerich, the Secretary General and Relator of the synod:

“It is in view of this Continental stage that we address all of you, who, in your particular Churches, are the principle and foundation of unity of the holy People of God (cf. LG 23). We do so in the name of our common responsibility for the ongoing synodal process as Bishops of the Church of Christ: there is no exercise of ecclesial synodality without exercise of episcopal collegiality.”

Yet as Luciani makes clear, this is not quite what synodality is actually about, because the priority of Lumen Gentium’s second chapter on the people of God means the hierarchy are in a subordinate position to the church as a whole:

“We cannot treat synodality simply as a concept derived from collegiality or conciliarity. It is not just a specific event nor a functional method. It is a constitutive dimension that qualifies ecclesiality and defines a new way of proceeding for the Church as people of God. Thus, it invites her to re-form by reconfiguring her into an ecclesial ‘we’, where all subjects, from the pope to the laity, are equals and articulated in a communion of faithful with the same responsibility regarding the identity, vocation and mission of the Church.”

He continues, in no uncertain terms:

“For many Catholics, even in the academy, it is difficult to understand synodality not just as a way of enhancing processes of consultation and listening in the Church, without realising the implications that is has for a permanent reform of the Church and for the way in which theology is done today.

This also means that the governance procedures of the church must be rethought. If synodality is not just consultation, but active decision-making according to the sensus fidei fidelium—the sense of faith of the faithful—then it must also be circular, dialogical and hermeneutical. Church decisions are not based on individual conscience, but on discerning the sensus fidei of the whole. And the sensus fidei is fundamentally a matter of what is meaningful to the laity, not what is true according to an external authority—whether that be ordained ministers, scripture or the Tradition.

Yet it’s not quite consensus or democracy either, because as Fr Rush says, there are certain hermeneutical meta-principles that decide whether an expression of faith is authentic ahead of time. Whether even these meta-principles will survive the synodal process in any meaningful way will be the subject of a future essay. One also gets into the odd position where the international theological commission’s 2014 document on the sensus fidei is also presumably received according to the sensus fidei of the people of God. Does the sensus fidei fidelium interpret and decide its own meaning, free altogether of external judgments?

To get back to brass tacks: how does this all work when votes have to be cast? After all, the greatest Australian thinker, NSW Labor Party divine Graham Richardson, discerned the greatest theological principle of all: doing the numbers. Luciani is open enough to say that synodality reverses the relationship between a consultative and deliberative vote at any council or synod of the church. This reversal was already discernable at the Australian Plenary Council.

The norm is for members to cast consultative votes on individual texts, and for the bishops to later cast their deliberative votes to accept the texts and bind the church. Yet in the lead-up to the Plenary the reform groups encouraged the bishops to merely ratify the consultative vote of the laity. On the Wednesday, when the bishops’ deliberative vote knocked back the set of motions on women in the church, a protest on the council floor led to “further discernment”, a reworked text and a further vote that passed the motions.

On the “naive” or plain reading, this meant that the rules were bent to accommodate a protest from a motivated interest group. The bishops consulted the laity, but ultimately decided to vote the motions down. That’s their prerogative; the people of God give their views, but it is the hierarchy who have the responsibility to “rightly divide the word of truth” (2 Tim 2:15).

But in a truly synodal model, the discussion among the people of God is the constitutive act when it comes to making a decision. The whole people of God is the subject that theologises, not the hierarchy. Thus, Luciani says, the consultative vote “represents the reciprocal relationship among laity, priests and bishops without which no consensus could be formulated. In this sense, it must be binding.”

This is the nub of the entire synodal project as it is conceived of by its proponents: that the deliberations, decisions, desires, governance etc. of the bishops do not reflect their own witness or conscience in the first instance, but rather are made from “within the people of God”. The real decision-maker is the church, conceived of as the whole people of God, not the bishops, and certainly not any one individual bishop.

Thus the Wednesday protest was a good thing, a “disruption of the Holy Spirit” that overturned the false vote of the bishops against the women’s motions. When the bishops retired for “further discernment” and the texts were rewritten, on the synodal reading this was an authentic response to the people of God’s dismay and another example of hermeneutical circularity: nothing meaningful to the people of God can be excluded. As with the relationship between council and document, the synodal reading aggressively precludes “naive” or plain readings of the Plenary Council’s proceedings.

The reversal in voting is also true of drafting. When in February 2022 I interviewed Bishop Paul Bird CSSR of Ballarat, the head of the Plenary Council’s drafting committee, I asked him whether the Plenary’s steering committee puts the motions to the council. He replied: “A text under each heading will be put to the Council. If you will, it’s the Council putting it to itself.” Thus the phenomena in which items excluded or edited out at one stage of synodal development re-appear in the next—like women’s ordination, lay preaching and other controversial proposals which were voted down at the Plenary, only to reappear in the synod on synodality submissions—is completely consistent with the synodal methodology. Just because a deliberative vote excludes an item at one stage does not mean that it is not somehow still present in the sensus fidei fidelium.

In this sense the divisions between consultative and deliberative votes, draft documents and finals, are all artefacts of the preconciliar age that may well have outlived their usefulness. Why does the church need an episcopal “house of review” if the decision is already materially made at a consultative vote, and the motions represent the fruits of the whole church’s deliberations and labour? If a document is “unfinished” even upon being published, because it awaits reception, then what is the difference between a draft and a final product?

Indeed, Luciani says that “the reform of mentalities must be linked to the reform of structures; what is more, a true synodalisation of the whole church can be carried out only in conjunction with an organic revision of the Code of Canon Law”. That a plenary council has a specific meaning in Canon Law was emphasised by some participants and simply ignored by others, who wanted it to be a “new Pentecost”. At the Plenary’s conclusion it was said by certain prelates that we had undergone a “Plenary Council in a synodal style”.

If hierarchy has only a purely formal meaning (or perhaps even a negative meaning) in all this—no true power to deliberate, no positive role for discipline—one begins to wonder: doesn’t this radically shift the meaning of ordination? The concept of hierarchy was coined by the 6th century monk Dionysius the Areopagite, who in his Ecclesiastical Hierarchy says that it does not refer merely to the ordained man but to the ordering of all holy things—namely the mysteries of the church, the sacraments. In the contemporary church, ordination is being decoupled from governance. If Dionysius is right, one would also assume that the mysteries themselves would be decoupled from the church’s ecclesiology. That is, a separation between ecclesiology and the eucharist would be introduced.

This is what Luciani, whose frankness is again very refreshing, explicitly claims. He says that the priest is “ordained primarily to serve the community and not to perform worship” and that the sacrament does not set the priest aside from the community, but rather subordinates him to the “universitas fidelium”. What does this mean except that the priest teaches the faithful, yet in a hermeneutical circle where he receives as he gives? On this model the priest’s teaching is a kind of “discovery” where he goes out on mission to find that those who are to be formed are already in possession of the faith, and indeed are those who determine its content. He teaches by learning, heals by being wounded and so on.

This means that the eucharistic and communion ecclesiology of last century is effectively over, to be supplanted by a mission of listening. Luciani makes this point with a quote from the Spanish theologian Santiago Madrigal:

“Thus, the common priesthood of the faithful is prior and permanent; it is never lost. Moreover, it is a prerequisite for attaining and exercising the ministerial priesthood. In summary, ‘the Vatican has made an option: its starting point is not the celebration of the Eucharist [worship] but the mission of the people of God, which implies recognising the ontological priority of the priestly people, within which priestly ministry is inscribed’ Consequently, the common priesthood constitutes the totality of Christifideles [Christian faithful] as a priestly community or people in and for whom the hierarchical ministry is exercised.”

Hence the emphasis on a purely baptismal ecclesiology—another key theme in synodal ecclesiology I will return to in a later essay. The eucharist must be displaced from ecclesiology, or priests will retain some vestige of protagonism. The argument goes further: if the priest’s faith and service is subordinated to the whole, this must also be true for each member of the people of God. Each Christian’s faith must be subordinated to this same consensus fidelium:

“Therefore, the belief of a single individual does not exist. The act of faith takes place in and as Church, in the form of the sensus fidei ecclesiae … Isolated individuals or groups that object to a culture of encounter, meeting, coexistence, and sharing will not accept communal forms of living and interacting; they will be lacking in synodal attitudes.”

To circle back to Fr Rush, Vatican II was a uniquely accelerated moment in the history of the development of doctrine that required new hermeneutical principles to be correctly received. For Luciani, this reception requires unique, fresh structures such that “ecclesiology becomes ecclesiogenesis”. The church is yet to be born (or born again). Synodality is finally actualising the latent dynamism in Vatican II, such that the Catholic Church will be totally re-formed from below in “a continual and communal process of ecclesiogenesis, that is, a perpetual state of conversion and reform”.

Thus a vision of synodality grounded in “hermeneutics as an ecclesiological style” can never be compatible with a “moderate” synodality closer to the letter of Lumen Gentium. There is no such moderate vision of synodality on offer, such that a new balance could be struck between the hierarchy and people of God on consultation, lay leadership and the like. Similarly, there is not a reasonable core of synodal moderates in power, who are being undermined and let down by radicals in Germany and the organised reform groups. As long as synodality presupposes the absolute ontological priority of the people of God for the reception of the conciliar vision and the discernment of the sensus fidei, there is no mean towards which Catholics formed by the vision of the last two pontificates might strive.

The implication also seems to be that to be outside synodality is to be aloof from the people of God, and perhaps even outside the church in a certain sense, if we conceive of the church as a synodal process of communal interpretation. To be blunt, there is no Benedict Option out there, no bolt-hole for Latin Mass trads or “reform of the reform” types who want to ride out the remainder of the synodal period. Nobody will go un-encountered.

Leadership in a Synodal Church—Revenge of the demythologisers

a terrorist of sorts,

from many perspectives, he was a failure

he defied death and yet lives on in his followers

Death did not kill him

death did not destroy his mission

to bring the kingdom of his God to realisation.

- Anne Benjamin

Synodal theology may propose an ecclesiology in which the Pope is equal to lay Catholics in the pews, but in reality the church is an institution requiring many layers of mediation simply from a governance perspective. With the priest and bishop now decoupled from governance, which class of person will take their place as vicars of the synodal church? Enter Anne Benjamin and Charles Burford, whose Leadership in a Synodal Church is a guidebook for the synodalisation of the professional-managerial class of facilitators, teachers, liturgical guides, managers of charities, secularised religious, Catholic professional services providers and sacramental co-ordinators.

The book begins with a salvation story. Christianity is experiencing a crisis of leadership after scandals, mismanagement and the COVID-19 pandemic:

The cracks and dissatisfactions within the Church have been there for years … It is very easy for those of us who are faithful committed members of our Church to imagine ourselves as lying under the rubble of a disintegrating apartment block, or swimming in the deep while being circled by sharks, trying to resist the inclination to let go, to sleep, to drown, rather than continue our efforts to be Church.

Instead of offering wise leadership, the church has lost its voice. “Some would even argue it has lost its right to have a voice,” the introduction says. Nevertheless the church remains alive beneath the rubble, still burning with desire to fulfil its mission. As with Fr Rush and Luciani, synodality activates this latent energy. In its practical application as a leadership style (as opposed to management or administration) it goes around doctrine to pay close attention to “the central role of culture in community”. In doing so, it will resurrect the grassroots by restoring the positive dimension of their lay identity—in Fr Rush’s terms as the receivers of the council, in Luciani’s language the Christifideles.

After an introduction to synodality, we get “The Back Story”—an account of Christian theology. It is only a back story because, as I detailed earlier, the hermeneutics of synodality and the mission derived from them take priority over the primary data of Christian faith. In any case, the account that Benjamin and Burford give of the economy of salvation has an extremely low and demythologised Christology, derived from the theology of Hans Küng and others like him. A few excerpts, with asides in brackets:

- The Holy Spirit “breathed into the hearts of those who searched for truth; and spoke to nations whose leaders yearned for wisdom and knowledge through prophecy. Then, in time, ‘God’s ever-present Spirit’ [not Logos] took physical form in a Palestinian called Jesus in an out-of-the-way village called Nazareth, and the action of God’s Spirit became the mission of Jesus”.

- During his public life “He began to teach as a prophet about God and God’s Kingdom … the Holy One of Israel was a God with whom Jesus was intimately close.” [One hopes so, given Christ was the Holy One of Israel.]

- Jesus yearned primarily for the defeat of suffering and evil and the soothing of woundedness, not the salvation of souls. He was opposed primarily by “religious purists” who were threatened by his radical message. “After about only three years of his teaching, healing and working with a small team of disciples, he was killed as a criminal. Yet, after three days, people saw him again, risen, alive.” [Note: he was not resurrected but “seen alive”. As Küng put it and Benjamin writes in her poem excerpted above, Christ "lives on" in the memories and spiritual experiences of his followers.]

- The church is an intimately shared spiritual experience, “called into existence by the mission entrusted to the early believers”. In other words, “the Church came into being because Jesus asked his friends to continue what he had begun”. The church is not an answer, but “a response”—a human response [perhaps a graced human response] to the mission of Christ, not a deeper mystical or ontological reality in conformity to his body.

- When it comes to leadership, one cannot simply imitate Christ: “There are considerable limitations and risks in attempting to look to Jesus to find what we would call ‘models of leadership’ appropriate for those in ministry.” Instead one might consider certain “leadership styles” derived from the New Testament, according to certain hermeneutical principles. Fr Denis Edwards is quoted, saying New Testament leadership is relational, non-violent, leadership from below, participatory, empowering, based on hope “in the resurrection of the crucified” [by which we mean the relief of suffering].

- Clericalism is a kind of master-theme that has “a direct bearing on the topics covered in this book” because it cuts to the core of who Jesus was, and was not: “Jesus was not a cultic priest.” [See among other texts Dr Margaret Barker’s The Great High Priest for the contrary view, that the cultic Temple liturgy was the sine qua non of Jesus’ identity.] He promoted women, “chided influential pedants”, “did not wear special garb” and was not clericalist.

- Diversity is therefore desirable, and polarisation into liberal and conservative camps is undesirable. The solution is to fully implement synodality, open the doors to all, and give everyone a seat at the table—even the “disenchanted and disappointed faithful”.

Everyone except newly-arrived migrants who bring pious attitudes to this country, one learns:

“The impact of ethnically diverse attendees might disguise some of the decline in attendance by previously long-practising Catholics. However there is a tendency for some newly-arrived groups to bring a desire for a pietistic experience rather than for an experience of a more-engaged participative Church, as promised by Vatican II. Some priests from overseas countries similarly have brought a similar preference for piety over engagement, participation and outreach.”

The rest of the book gives activities, guidelines, strategies and tools for synodal leadership. The theological and salvific “back story” recedes in favour of secular theories of governance, diagrams of values hierarchies, and models recommending transformational and subjective styles of leadership. All of this is done very competently—the authors are well versed in the material. Yet their approach leads to the odd situation where the One Lord Jesus Christ can be described as a “failure of sorts” and a problematic model for Catholic leadership, but Jacinda Ardern, Nelson Mandela and Martin Luther King Jr. can be recommended with enthusiasm as models for imitation.

It is absolutely crucial for the synodal theology to be able to explain disjuncts like this if it is to become a living theology for the church, rather than a process. We might remember that Jesus Christ was not the incarnation of a "value", but it could be argued that Jacinda Ardern is just that. In dozens of similar moves throughout their guide, Benjamin and Burford cut to the heart of what the synodal project really means. At the “grassroots”, synodality (in Australia, and perhaps the rest of the developed world) means the consolidation of the Church’s missionary effort into corporatised agency structures stripped of the primary data of faith and instead supplied with values, principles and secular guides. As the authors write, “mission finds expression in ministries”:

“[T]here is a measure of formality in the call to ministry, either through ordination, consecrated life, or commissioning to roles such as pastoral associate, school principal, pastoral council member, agency head. It is easy for us to see how the ‘Kingdom’ inspires the Church’s agencies of social services, education, healing, community building and working for justice.”

Is it contrary to the spirit of synodality to point out that many of the greatest Christian thinkers throughout history—from St John Chrysostom to Fyodor Dostoyevsky and Ivan Illich—have said that the institutionalisation of Christianity is the church's greatest betrayal of the Kingdom of God, not its fulfilment? This is not to say that we must be so categorical, but should retain a healthy regard for the limits of majorities, consensuses, sensus fidei omniums and their corresponding structures. Indeed it is another oddity of the synodal theology that at the exact moment the church's formal ecclesial structures are being subject to withering criticism in practically every denomination, its corporate structures are being held up as a better way of being church. This is surely not a coincidence.

The most significant of these emerging structures is the Ministerial Public Juridical Person (Ministerial PJP), an entity established by a religious institute to carry on its mission, employing lay staff and governed by a board of directors. “The establishment of Ministerial PJPs, being relatively recent, has been very deliberate with a high level of attention given to their mandates, their delegations, relationships and governance structures,” Burford and Benjamin write. These PJPs give a new lease on life to ministries that can no longer be staffed by consecrated religious, and in this sense offer a genuine way to continue good works that might otherwise die out. Yet they have another benefit, by virtue of their governance structures they are functionally immune to cultic and clerical influence. Their rationale is, after all, to transform religious congregations who do not attract vocations—now re-interpreted as a positive sign of God’s desire to dispense with outdated structures—into NGOs with employees, governed by mission and values statements. A worker in a Ministerial PJP, as opposed to a monk, does not evangelise by prayer, or preaching, but by offering relief to those suffering or experiencing a lack—in other words, by doing care work in a services economy.

Again, this is not to denounce the management technologies of the current age as somehow irredeemably fallen. But a certain critical distance is necessary, because workers in Catholic agencies—PJPs or otherwise—are also the people of God, the primary subjects of theology, who constitute the church and participate in the synod process, sometimes as part of their paid employment. According to a maxim of St Thomas Aquinas’s quoted by Fr Rush, Luciani and other synodal theologians, things are received according to the mode of the receiver; thus the meta-principles of synodality are received at the lower level among the professional-managerial class of the church, who then feed their interpretation back to the synod process through the various listening sessions and consultations endemic to this kind of ecclesiology. As with the rest of life in Australia, the professional-managerial class has its own style, language, priorities and desires. Without putting too fine a point on it, this class tends not to dwell in the suburbs of our cities where rates of religious practice are highest.

Yet in terms of the synodal theology this is hardly a problem, because given the decoupling of ordination and eucharist from governance, the ecclesiology becomes hyper-missionary. Indeed the difference between the church ad intra and ad extra is said to collapse; it's just mission all the way through. In this sense, the experience of working for agencies becomes the primary mode of “being Church”—not worship, prayer, asceticism, the reading of scripture, the remembrance of the saints, or even preparation for death. As St Vincent de Paul national president Clare Victory said in the lead-up to the Plenary Council:

For a lot of people, the agency, the organisation in which they’re involved, the Catholic school community they’re part of—that is Church to them, and that is the truest and most authentic expression and reality of their Catholic faith.

On the synodal reading this is because the mission of the church must adapt to the concrete structures of the world that receives the Gospel, the reception of which informs the content of the Gospel itself, and so on, and so forth, in a never-ending hermeneutical spiral.

Squaring the hermeneutical circle

To return to the original thesis—that synodality is the triumph of hermeneutics as an ecclesiological style—what greater confirmation of this could be possible than the idea that working in the services economy and attending listening sessions is the fulfilment of the great commission, and perhaps even the primary experience of “being church”? An interpretative apparatus of frightening scale and power is needed to convince a person that God in the flesh was put to death for this outcome. The prophets and saints “of whom the world was not worthy”, who sheltered in dens and holes in the ground, were beheaded, put to the sword, sawn in half, tormented (Heb 11:37-38)—are their true successors of really the hermeneuts and leadership trainers? Are mission statements the true development of the Nicene Creed, of Chalcedon, of the doctrines for which countless martyrs were willing to go to the rack?

This is not to say that the church oughtn't have its own knowledge workers, managers, technicians, accountants, lawyers, charities, agencies and the like. Jesus Christ came to redeem all this too. But we are called to be co-workers with God in building the church's structures such that they image God's own Kingdom in this world, as a foretaste of what is to come. The people of God already have representatives and mediators that God has called and appointed; they are not primarily delegates of the community, even though warrant from the community is vital for them to fulfil their mission. To replace these with members of the ascendant class in globalised post-industrial service economies, and to substitute the primary data of faith for principles of interpretation—these are really quite significant reforms that warrant a lot more open discussion.

To anticipate two initial objections before concluding this first section:

1. I do not think the way forward is to promote a plain reading of the texts, including the documents of Vatican II. In fact, it seems to me that it is the proponents of such an approach who are embroiled in an epistemic crisis of the sort Alasdair MacIntyre raised in his various works: if they cannot raise answers to the synodal theology, the argumentative power of their witness to faith will fade. Restating the status quo ante will no longer suffice.

2. The hermeneutics of Gadamer, Paul Ricoeur and the like are not the only interpretive strategies open to us, and may not even be the most compatible with the church’s tradition. Indeed, the hermeneutical enterprise tends to disintegrate into a kind of benevolent nihilism that tries to free us from the “temptation of realism”, as Gianni Vattimo’s weak thought philosophy has shown. No attitude could be further from the Christian Gospel, but is thoroughly congruent with the conditions of postmodernity identified by Fredric Jameson as the cultural logic of late capitalism—the triumph of free-floating signifiers, fungible "values", ironic detachment and so on. I will return to this in a forthcoming section, where I will lay some of my own cards on the table. ◼️